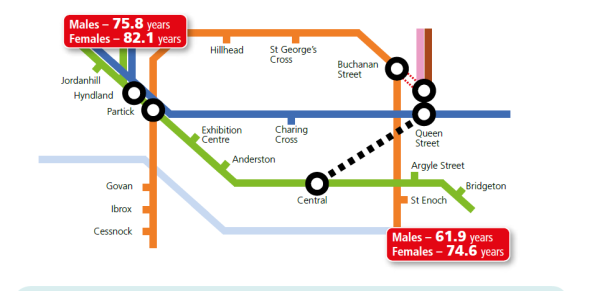

The train line pictured above is one that I often take in my home city of Glasgow. It takes 19 minutes to travel the 6 miles or so from Jordanhill in the west end of Glasgow to Bridgeton in the east end. In a remarkably illuminating piece of analysis, a Scottish health researcher used the rail map of this train (above) to reveal that life expectancy in men decreases by two years with every station you pass on the journey. The researcher, Gerry McCartney, highlighted that the average man in Jordanhill can expect to live 14 years longer than his counterpart in Bridgeton.

It is a shocking graphic but it exemplifies and reminds us of the grave inequalities that are damaging our society and our economy today. Yes, most people now have smart phones, can access the internet, eat exotic imported foods, travel across the country on public transport and have access to comprehensive free healthcare. The overall living standard, wellbeing and prosperity of the UK population as a whole is beginning to recover again after years of difficulty in the wake of the financial crash. However, we have not all benefited equally from society’s advances. A trend in recent decades has emerged in that the gap between those at the top of society and those at the bottom is widening: ‘the tide is rising but not all boats have been lifted’. Any growth in the UK economy- and most other developed nations- appears to be disproportionately benefiting those at the top.

Is it the case that as members of modern, developed capitalist countries we have become inured to the notion of inequality? There are certainly those who accept the abridged standard argument that the nature of our free-market economies will inexorably lead to some people becoming rich while others will be poor. The assertion is that this is because some people will work hard while others do not. And is justified by the idea that some people will rise to the top but others still have the chance to do so. Worryingly, however, in recent times this topos has become exaggerated beyond recognition and the logic chain now seems to be perverse. Inequality has become so great that the there is no longer a connection between bottom and top; and as a consequence, there is no longer a path between them either. As such, troubling, polarising situations are arising like the divide displayed in the train map. This is not just a divide between rich and poor but a gulf in the quality of life experienced by members of the same community living 19 minutes apart.

The gulf can also be seen in education as well as in health statistics. Another Scottish researcher, Lucy Hunter Blackburn recently highlighted that 18 year olds from the most advantaged areas are still more than four times more likely to go straight to university than those from the least advantaged areas. Neither is this a problem limited to our country or our society. According to Oxfam, the richest 1% of the world’s population now own more wealth than the rest of us put together.

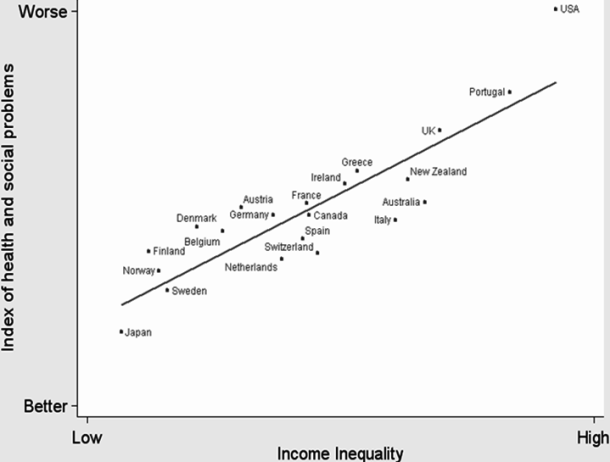

This gross inequality is clearly not beneficial to society; a notion that is becoming the global consensus, uniting figures as diverse as the Pope and the IMF. The widely respected Economist magazine recently concluded that “inequality has reached a stage where it can be inefficient and bad for growth”. The former chief economist of the World Bank and Nobel Prize laureate, Joseph Stiglitz frames it bluntly: “Widely unequal societies do not function efficiently, and their economies are neither stable nor sustainable in the long term”.

Drawing on Stiglitz’s thesis, highly unequal societies are not efficient predominantly because of the lack of upward social mobility. The fact that only one in five low paid UK workers in 2002 had managed to escape low pay by 2012 means that our lowest qualified workers are not developing. A huge proportion of the workforce is stuck in sectors with declining employment and with little transferable skills to take them to new jobs. It is not just these people in the lowest echelons of society who continue to suffer, however, as we are also beginning to see a hollowing out of the middle class. UK median incomes have faltered, while the number of billionaires in the UK has doubled since the financial crisis.

Looking past the negative economic impacts of this cataclysmic divide in society, there is also the outcome of unstable, political and social unrest. A revolt against the establishment such as the recent Brexit referendum was perhaps inevitable given the growth of such vast socio-economic divides. President Obama of the United States- a country even more unequal that our own- appreciates this sentiment and worry, underlining that “Inequality is the defining challenge of our time”.

So the obvious question remains. What can we do about it?

I believe we should start by acknowledging the basic flaws with a ‘trickle down’ approach to the economy. No longer can we assume that by being generous to those who create jobs- the already wealthy- will this actually result in more jobs being created or in prosperity being shared. In fact, concentrated wealth at the top is less likely to result in the kind of broadly based consumer spending that often drives our economy, and together with lax regulation, may contribute to risky speculative bubbles. The global recession in 2008/09 that we are only just recovering from was sparked by those very factors.

We should also recognise new developments in the way our economies work; including the politically relevant notion of globalisation. Large multinational firms trading across continents let alone countries seem all too easily able to evade accountability and basic civic responsibilities such as paying taxes. Similarly, in recent years there has been a dangerous shift towards the interpretation of workers as another form of capital: in the UK this has manifested itself in the rise of zero hour contracts. The argument is that a more flexible workforce will be more productive; but do the benefits derived from the certainty of a fixed job not outweigh this? With more certainty people will be more likely to spend and be given grants for loans, while they will also have more of a chance to get on the housing ladder- the first step in lowering the divide in wealth inequality. Moreover, workers are after all people and should therefore not be treated with the same sterility that one would approach a broken machine, axing them almost instantaneously when their usefulness expires. Furthermore, increasing the ‘lag-time’ of workers being made redundant will help to reduce the impacts of unemployment as workers will have more time to adapt to seek new employment.

We do not have to strike a Luddite attitude in the face of such developments but we do need to adapt and to ensure our economy works for all, not just the few. If inequality is indeed damaging to all of us, then we should start by reducing the gap between rich and poor. That does not mean holding back the successful, but it does mean ensuring the worst off are the biggest gainers in times of rising prosperity. We need to make the case for decent work, fair salaries for those at the bottom as well as for those at the top, and for redistributive taxation paying for public services shared and used by all. What is more, improving social mobility should be a stated aim of public policy in areas such as education, health and housing and not just the economy.

Returning to the Glasgow train map that inspired this article, it is clear that few people would condone the 2 year drop in life expectancy associated with every stop eastward from Jordanhill to Bridgeton. However, the effects of inequality are wider reaching than this morbid metaphor. As we have seen, gross inequality will lead to slower growth, a tendency towards a boom bust cycle, the vicious entrapment of those at the bottom of the social ladder, an increase in populist extremism and poorer community relations.

These problems affect us all and the solution is therefore complex; but what is certain is that, in the long run, a social attitude change is required. We not only need this shift towards a greater intolerance of inequality to drive the structural reforms and policy discussed above through our parliaments, but changing approaches to the prevalence and depravity of inequality will create a society that is more excepting of one another: ultimately rejecting inequality from the ground up. This conclusion can only enhance the growth our economies, improve living standards, and make our society’s fairer. A winning combination that most would believe in and that we should actively strive towards.

http://www.politico.com/story/2013/12/obama-income-inequality-100662?o=0

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/11627719/Social-mobility-has-come-to-a-halt.html

OECD.stat

Joseph Stieglitz- The price of inequality

NHS Scotland health inequality

Gerry McCartney – http://jech.bmj.com/content/65/1/94.extract

Lucy Hunter Blackburn – http://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Access-in-Scotland_May2016.pdf

Hi Douglas,

I really enjoyed your piece, and I’m happy to see this blog get some attention again. Keep up the good work! I don’t per se have any qualms with your analysis, but there are a few questions that I’d like to raise or ask about, if only for you to ponder in between or during economics lessons (incidentally, the methodology of the paper that you cited is called instrumental variable regression analysis, which is econometrically neat and can even – shock horror! – be quite amusing). I think it’s highly interesting, by the way, that even a paper with as obvious an ideological slant as the Economist would openly pillory inequality nowadays (Stiglitz and Obama, on the other hand, are merely playing par for the course) – do you think this incidence could and should be generalised, and, if so, to what extent? Further, what do you think about the ideological traction of the idea of trickle-down economics? As far as I know, Trump – who will doubtlessly be the chief advocate of the same over the next few years – doesn’t even have a clear ideological line on it.

First, the obligatory Brexit question: To what extent do you think this level of inequality, aside from global/regional/sectoral trends, will be affected by Brexit, if at all, and why? I would in particular highlight the political economy here, and the likely dominance of the Tories in UK politics over at least the next three, if not eight years.

Second, why do you think the ideological response to the Great Recession from the Left has been this muted? Why has capitalism as a method of resource allocation not been fundamentally challenged (or would you make the claim that it has been)? Given the typical sociological interpretations for the rise of revolutions – essentially an exogenous shock to the social system inducing relative deprivation, dissonance between expectations and reality, or some sort of social disequilibrium not countered by existing social institutions upholding the status quo -, why has there been this little unrest? Given Brexit, Trump, the rise in popularity of Putin and the general rise of the European far right, one surely cannot claim that the Great Recession was simply too small a shock. (One could make the frog-in-a-boiling-pot argument, but surely the Great Recession ought to have worked as a wake-up call in that regard, no?)

Third, and still relatively closely related to the topic at hand: What do you think the impact of the rise of superstar economics will be with regards to this sort of inequality, and what can be done to counter it? By superstar economics I mean the increasing capability of the world-best in their respective fields to leverage their abilities worldwide via the internet.

Fourth, and more generally, and perhaps wrongly: What do you think the relationship is between this rise in inequality and (what I see as) British aspirational elitism, or perhaps aspiration to classism? This is a theory that I’ve come to during my time in the winter wonderland bubble that is Oxford, and what I mean by that is that many Brits seem to aspire to the standard of living and way of conducting oneself that is emblemating of the British upper class, complete with weekend get-aways to Ascot and comparables in white tie and frock. (Think of it, perhaps, as a British perversion of the American way of thinking that sees oneself as a millionaire-in-waiting.) There is further another aspect to this, seemingly completely counter to the above, namely the apparent obsession of many millenial Brits to dress trashily for fun. This may just be a figment of my imagination, but do you think this manifestation of the classism of British society might in some way be impacted by this massive rise in inequality that you’ve highlighted?

Kind regards,

Felix

Hi Felix,

Thanks very much for giving your time to write such an insightful response; I really enjoyed reading and learning from the questions that you have raised (on everything!). Sorry it has taken so long for me to reply but my original response didn’t send and then I thought that I would add a bit extra.

Anyway, I will try to respond as best I can to each individual topic that you brought up. Hopefully I have offered at minimum my (vaguely correct or at least interesting) thoughts on the ideas that you put forward.

Your first point about potentially generalising the notion that inequality is harmful and should be pilloried- as suggested by The Economist- was in fact one of the purposes of my article. By citing organisation and figures such as the Economist- who tend not to offer a definitive ruling on a subject, instead opting to objectively provide the analysis for judgements to be made-, the supposedly impartial IMF and Barack Obama I hoped to show that extreme inequality is widely accepted as being harmful: it is not just the view of a few fringe political figures that excessive inequality is bad for economies and societies. This being said I also wanted to convey the problems that inequality can create in a relatable and truly eye-catching manner. I believe that the train map or the piece of ‘instrumental variable regression analysis’ would achieve this; ultimately acting as a morbid metaphor for the general and growing socio-economic problem of inequality.

You mention trickle-down economics and while I can’t say that I am an expert in the theory or practice behind it, I would certainly not advocate it if I were to have any position of power. Perhaps it works in theory, but – as is often the case in economics- there is a lot resting on some challengeable assumptions. Namely, the belief that policies such as cuts to corporation tax will encourage entire firms to develop and hire more workers; not just feed the profit machine that works for those in power. Moreover, one could take a more cynical view and state that Trickle-down economics is used merely as justification for the already wealthy and powerful to increase their standing. It is worth noting that most of my views on this matter are the product of reading works by Joseph Stiglitz, as such my conclusions may be a little skewed to one side of the argument.

Nevertheless, I am particularly drawn to some data regarding the Reagan presidency era. Trickle-down economics rules that Reagan’s lower tax rates should have helped all income levels rise- yet this is certainly not the case. Between 1979 and 2005, after-tax household income rose 6% for the bottom fifth. This sounds okay until you see that the top fifth had an 80% increase in income. While the top 1% saw their income triple. There were clearly other factors at play over this time but I believe that Reagan’s implementation of Trickle-down economics was a major part in the growing inequality of the era and that a Trump presidency could have similar consequences.

The classic Brexit question is always a difficult one with all the uncertainty looming. I do not think that Brexit itself- by that I mean the UK leaving the single market- will have much of an effect on inequality. In fact, perhaps we will see an increase in wages for the lowest paid workers in the event of a cut down on immigration and a shrinking in the supply for jobs. However, I am sure that the trend towards reactional, partisan and nationalist politics that Brexit perhaps represents will do nothing to aid the movement against growing inequality.

Like most people at the moment my mystic ball for telling the future is a little cloudy, but I definitely cannot see the needed shift in political focus to fight inequality when there is so much attention on dramatic constitutional changes. Further to this, the uncertainty surrounding Brexit is unlikely to have a positive effect on the UK economy. With firms potentially losing business or facing increased costs, I think it is likely that it will be the lowest paid workers and the poorest members of our society who will be the ones faced with redundancy or weaker job prospects. What is more, the apparent turmoil of the Labour party looks like it might leave UK politics dominated by parties less likely to counter the disparaging effects of inequality over the coming years. With voices of extremism coming from both sides of the political spectrum and an increase in nationalist arguments across Europe I do not believe that Brexit or the state of current politics is at all encouraging in the argument for more equality.

The next point you raise, regarding the muted response from the Left in reaction to the Great Recession, has made me think the most. I am genuinely unsure why the response to the greatest exogenous shock of our time has been met with such little revolt from the left of politics. One would have thought that the wake of the worst recession in decades primarily caused by unchecked lending and market speculation would have been an ideal time for the centre-left, as critics of free markets, to capitalise. Instead the political reaction seems to be perverse; growing nationalism and right-wing policy looks to be the future.

This being said, perhaps it is possible to rationalise the global political reaction to the Great Recession. It appears that voters- rightly or wrongly- have blamed their respective incumbent political party for the negative effects of the weak (or negative) economic growth. In the UK this meant that the Labour party was seen to be at fault for the economic turmoil post 2007 and was accordingly ousted by the right-wing Conservatives at the next general election in 2010. While in the US, the Republicans were replaced in the midst of the Great Recession by the more left-wing Democrats. This pattern, of the current political party being replaced by their opposition (irrelevant of political preference), appears to have been replicated globally: countries such as Germany, Japan, and New Zealand also turned against the pre-crash government. Perhaps all we can draw from this is that voters take a very short term view of the political and economic situation; quickly moving against the establishment in times of vicissitude even if the blame lies elsewhere.

Nevertheless, this does not account for the continually growing strength of right-wing and nationalist parties across Europe and the world at present. I cannot answer why the left has not offered a clearer, brighter picture of the future they would hope to create, but I believe that people have been drawn to more extreme solutions since the Great Recession. My explanation would be this: with almost an entire decade of lost real income growth, many people’s living standards and livelihoods have stagnated. Discontent with the status-quo and looking for some sort of tangible improvement in living standards, the right of politics seems to have provided a more radical and short term fix ‘for the people’ (to quote Donald Trump and Bane from Batman). In other words, the anti-immigration and inward looking tendencies of some right-wing candidates looks to have captured the growing discontent of the lower and middle class much better than the often strikingly omniscient members of the liberal elite. Moderate liberal rhetoric has fallen on deaf ears following the noise created by the Great Recession.

My last response to your question has left me with further questions that I am thinking of addressing in a future post. Similarly, I will answer the rest of your propositions as soon as possible but I hope that what I have said so far is decipherable and vaguely reasonable.

Thanks again for your time and feedback,

Kind Regards,

Douglas

Dear Douglas,

First of all thank you very much for this insightful and thought provoking article. Much like Felix I am quite happy to see the blog coming back to life!

During your analysis you quote an Oxfam statistic – “the richest 1% of the world’s population now own more wealth than the rest of us put together.“.Oxfam frequently calculate such figures. Most recently they published the following claim: that the eight richest men in the world, between them, have the same amount of wealth as the bottom 50% of the population combined. On the face of it that statistic is disturbing. However, when we actually crunch the numbers it appears a bit too disturbing: The eight richest people in the world have a combined net worth of roughly $426 billion, or 0.16% of all the world’s wealth. This would imply that the bottom 50% own 0.16%. Why is the number this low? Oxfam includes debt in its calculations, giving a good chunk of the population (in context of the analysis) negative wealth. According to Oxfam’s methodology, the bottom 10% of the world’s population has a net worth of one trillion negative dollars. By that metric, I am poorer than a Syrian refugee because of my student loan. To me, this appears counter intuitive. My first question to you would then be: Do you think Oxfam should include different metrics to measure wealth and inequality? Potentially relative measures within societies?

Furthermore, it is evident that the methodology of the Oxfam statistic is making for a very good headline promoting the flight against inequality – a good cause. On the other hand, the methodology is rather questionable. So the crux is: Does the end justify the means? Is it justifiable for Oxfam to „fudge“ its data analysis to make its case look stronger? What do you think?

I look forward to your reply and keep up the good work!

Best,

Carl

Hi Douglas,

Thank you again for that response – it wasn’t just decipherable and vaguely reasonable, but also unjustifiably interesting!

A few disparate thoughts on your response below:

I’m not sure to what extent the analysis by the Economist can be called objective. This isn’t one of the trope attacks on the subjectivity vs objectivity argument that I cannot comment on to a much greater extent than whatever epistemological philosophy my intuitions and sporadic readings over the years can yield, but instead what I mean by that is that the Economist follows not just a very clear line, but also a very clear layout of articles. (I once had to analyse their journalistic style in one of my internships, finding it actually quite funny how repetitive it can be when it comes to certain topics – company profiles, for example, always focus on a particular item in the factory, characteristic of an executive, location of a factory or the headquarters, or trope about the country of origin or production that can be generalised or refuted in the analysis, which always seeks to extol the virtues of liberalism, free-flowing thought, or cutting-edge ‘establishment radicalism’). What would actually be interesting to know is whether writers there are given centralised directions or whether this is the result of minds simply thinking alike – one of those (in-)famous echo chambers, if you like.

NB: This is not to say that it is a bad newspaper. As far as newspapers go in the English-speaking world, it probably is among the top three to five. Its briefings, columns, and special reports are particularly good. If you don’t yet have your own subscription, I would recommend it to you heartily.

There is a dichotomy, I’ve long thought, in academic economics and related social science disciplines between the theoretical purity of a line of thought or particular section or strain of economics academia globally, and its applicability in the real world. This comes out perhaps most starkly when you contrast (Neo-)Keynesian analysis with Neoclassical models such as the Real Business Cycle, which, to tell the truth, is mathematically wonderful but so far removed from reality that the societal challenge to economists’ self-justification – defined as, say, bettering the workings of the economy and/or society via analysis and policy recommendations – ought to really be negated just on these grounds. What use is it, after all, if one is working away on theoretical perfection in some ivory tower behind gold-plated oaken doors that then turns out to be generally useless to society at large, or whoever one is beholden to as a professional economist? I would cite Keynes’ words here, urging economists to be philosophers, mathematicians, historians, and statesmen. (When you think of it in these terms, it also becomes quite interesting what the choice of mode of analysis – Classical, Neoclassical, Neokeynesian, whatever you really want – says about the author and his (or her!) political and socio-economic predilections.) This must surely also be one of the reasons why economists suffer from such physics envy – if only things were as straightforward and mathematically reducible as the physical world!

In your discussion of Reaganomics you yourself acknowledge that there are many confounding problems when considering income growth since 1979 – this, I think, is correct. These days, I am frequently reminded of a chart that I’ve seen time and again about the dichotomy between, I think, either median or mean average household pay and productivity, which grow in perfect harmony together until about the mid-1970s, after which point productivity continues to climb up and pay stays almost completely flat for the next forty years. Why this is, exactly, I cannot say. I’ve seen explanations that referred to the collapse of Bretton-Woods or Reaganomics, to automation or the oil shocks, to central bank independence or the decline of trade unions – I’m not sure, honestly, that there is a good explanation for it out there currently. It’s one of the great puzzles permanently at the back of my and likely many others’ minds. I agree with you, by the way, that the Trump presidency heralds little good on this front. I’m also not entirely sure what to make of his economic plans. Perhaps that might be another potential blog post? Or, possibly, an analysis of Trump’s style of politics as seen through the game-theoretic lens of a businessman?

Regarding the ideological response to the Great Recession, I should say that I’ve, in the meantime, found a paper on this topic by Schularick et al (an awesome German economic historian at the University of Bonn, if you care to know). I’ve not yet had the time to read it, but here would be the link: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/123202/1/cesifo_wp5553.pdf

A quick skim-read tells me that they find that the vote share of the far-right increases dramatically after financial crises, but not after normal recessions. However, the authors don’t offer an explanation as to flimsy left-wing ideological responses to financial crises – this in itself could also be quite an interesting phenomenon. My instinct, based on the knowledge of left-wing ideology in Europe, the US, and Japan in the 1920s and 1930s, and Europe and the US today, would suppose that it, to a large degree, has to do with the fractionalisation of the left-wing itself, the appearance of indecisiveness, party infighting, or similar phenomena – but that could be as good or bad as anybody’s guess. (What is also really interesting to note here, though, is that, if I recall correctly, the US economy has historically statistically grown faster under Democratic presidents than under Republican ones. The Economist did a piece on that once, I think.) What is also possible is that the often purely or largely distributionist rhetoric of some left-wing parties doesn’t draw the same emotional connection from the crowd as the ‘let’s-all-move-together-against-the-foreigners/immigrants/others’ rhetoric of the far right.

Kind regards,

Felix

Dear Felix and Carl,

many thanks for your comments here. There is no quicker way to develop writing style, evaluation and research skills than having to defend a piece of work in a public forum. Your posts will really help Douglas.

Hope all is well,

WJJC

Hi Carl,

Thanks for your response.

I too have seen Oxfam’s seemingly continual display of more and more shocking statistics, and was actually wary of including the ‘1%’ figure in my original article. I did not know how the figure was calculated and thank you for clarifying that. I agree that including debt as negative wealth could in fact be counter intuitive; especially in a world based on debts through credit cards, mortgages, vast government borrowing etc. It appears that, using Oxfam’s current measure, someone with a decent job, lives in a country like the UK but who has a mortgage may well have a negative wealth- even though this person would be relatively well-off by global standards.

To address this problem I agree that relative measures could be the answer. Although, I also believe that something of a global relative would be needed as there is going to be so much divergence between countries. For example we could say that someone from Malawi (country with the lowest GDP per capita) who is literate and has a steady income through a teaching job would be incredibly well-off compared to most in their region; yet they still might not have proper healthcare, consistent access to clean water and so on – necessities someone in the Western world would take for granted. Therefore I think we would still count them as poor or underprivileged but to what extent? They might have similar incomes to people in other countries but nothing like the opportunity of upward mobility or access to high quality infrastructure- roads, schools, hospitals etc. For this reason I could see a lot of problems and therefore debate arising when using some form of relative measures. This will likely undermine the findings that data reveals as an easy counter argument can be made to question the assumptions underpinning it.

I guess my answer is this then: if you can find a way to measure relative wealth globally that is widely accepted then this should definitely be the way forward. However, I am not sure that it is possible to do and so I find myself coming back to using the original metrics. If you could suggest a better alternative I am sure that I could be easily persuaded.

Your second question- the most interesting question for me- is the moral dilemma of whether, as you say, to ‘fugde’ the data in support of a good cause.

As I mentioned earlier, I thought about this before and quarrelled over whether or not to include the data that I knew was potentially suspect. Yet, driven by the want for catchy statistics that were going to back up my argument, I included it. This does seem quite hypocritical of me, but it appears that I have fallen into the easy trap of only sharing the argument that supports mine; something that I will discuss later.

I don’t believe that Oxfam’s measure really is that bad but for arguments sake lets say it was a complete reworking of the facts to only reveal what I wanted it to. To what means is it justifiable to do this? There are always going to be situations where you are in a position of power and what you say (or don’t say) is going to have influence. I can’t offer a definitive answer on this but, paradoxically, by twisting the truth are we not corrupting the equality that the article wants to pursue: the audience is not given the all the information in case it makes the ‘wrong’ choice.

This seems particularly topical at the moment with the continual ‘Fake News’ controversy, allegations surrounding false Brexit arguments and Donald Trump’s entire approach to the truth and to news. The recent, rather petty, stint by Trump and his team was to claim that his inauguration was “the biggest ever”. We have seen that it wasn’t but why would they so blatantly lie. There are a lot of filters in our world, through the media and the internet and now it seems that we cannot trust exactly what the leader of the free world is saying. If he can so easily lie over something so trivial then the question remains that what if he really needs to lie about a much more important topic that may harm the public? Also what of the example that this sets for the public and those who may have similar power to influence others: can they just say whatever fits their argument?

Perhaps then the answer is zero tolerance: No little small untruths about the size of a presidential inauguration or about the extent of wealth inequality. Once the line is crossed everything blurs to allow for much greater inaccuracies to be presented with much graver consequences. I am not sure if I totally agree with this argument, however, as there are definitely circumstances where a minor ‘fudging’ of the truth has much greater upside than downside. Yet, I would say that the more power and influence that an individual or an organisation may have then the greater precedence there is for the complete truth to be told.

My apologies for offering such vague answers but I think that the nature of your questions leads to subjective responses such as mine- or at least this is my excuse for knowing exactly what to reply.

Thanks again for your time and response,

Douglas